A Philosophical Happy Hour on theories of perception and their influence on our understanding of reality.

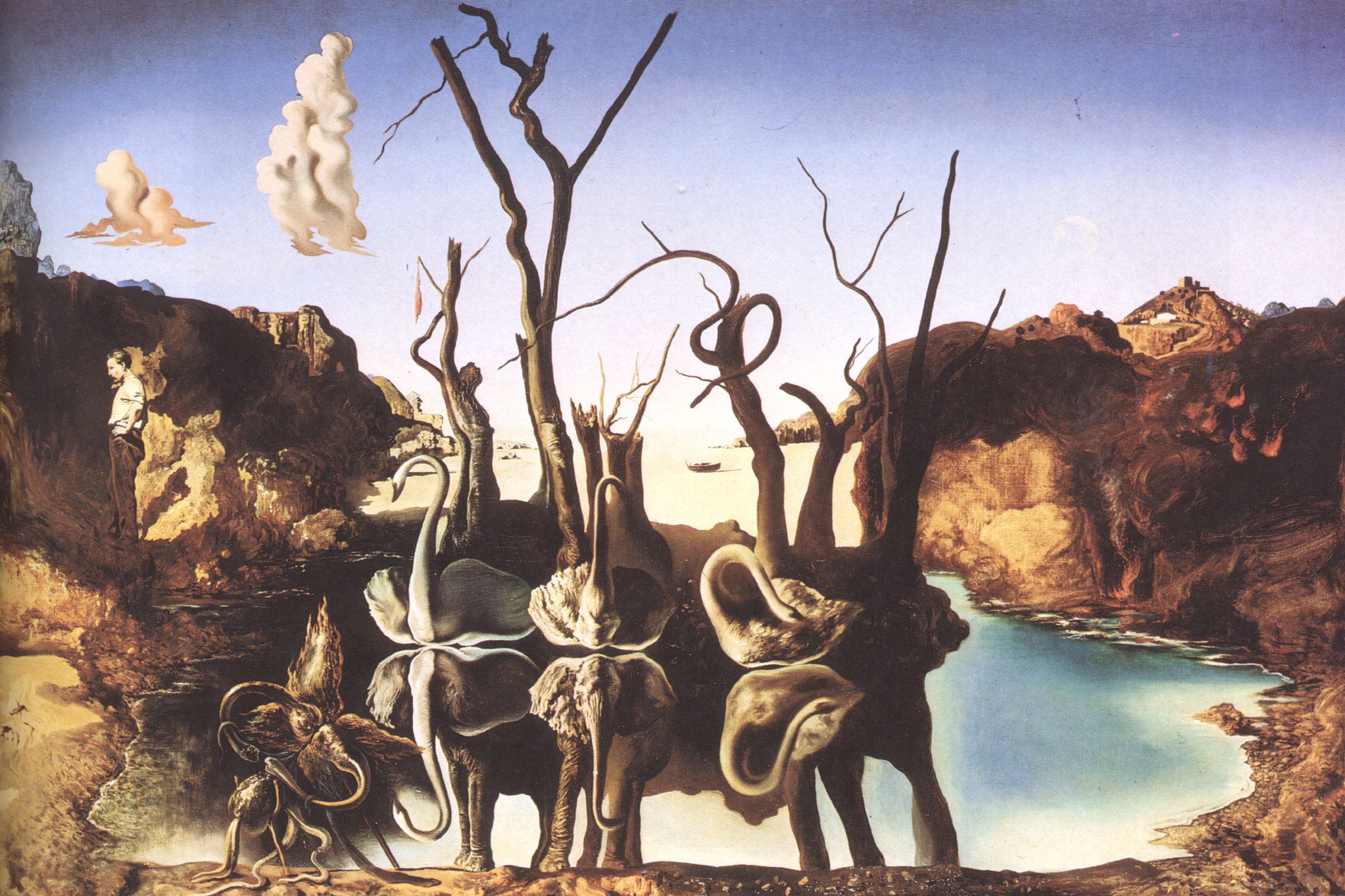

What if the world you believe yourself to see, to hear, and to touch isn’t the world at all, but only a clever illusion fabricated by your brain? The familiar colors, sounds, and textures that feel so immediate—it has been claimed—may not belong to reality itself, but belong to an internal model. The perceptual world would therefore constitute an evolutionary “user interface”, designed to keep you alive rather than to disclose the truth. According to such a theory, perception is not a window onto the world but a screen upon which images are deceptively projected, a virtual display constructed by neural processes.

Could the givenness of the perceptual world be only the most fundamental of illusions? If our perception of the world is only an illusion, what does this mean for our experience? What effect does this have on our consciousness? What, then, would it mean to be “aware of…”?

The Concept of Perception

This view—that our apparent perception of the world is only an illusory re-configuration produced by our brains—has become common over the past several decades. On the one hand, the belief that we live in a world of perceptual illusions is ancient. Plato’s cave comes to mind, as might Cartesian doubts and malignant demons. On the other hand, the neuroreductivist explanation, namely that these illusions are produced by our brains, is quite recent. It has the allure of being “scientific”, and the advantage of proposing “causal mechanisms” for the phenomena of experience.

There are, of course, other concepts of perception. The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty dedicated much of his career to investigating the nature of perception as a pre-conceptual and embodied engagement with the field of experience. Charles Peirce, the founder of semiotics, not only founded his thinking on a sophisticated phenomenology (or “phaneroscopy” as he sometimes called it), but posited esthetics as the first of his “normative sciences” (“esthetics” here comprising the original Greek sense of aesthesis, i.e., perception). Aristotle takes up the question of perception across not only several chapters of his On the Soul, but also writes a short treatise titled On Sense and What Is Sensed. Thomas Aquinas takes up these Aristotelian texts in extended commentary. And the psychologist James J. Gibson proposed a complex theory of sensory perception that emphasized the total engagement of the observed environment over the distinct sensory impressions that we receive.

What difference does it make whether we believe perception really relates us to the world or only presents us an illusion? One might say: it makes all the difference.

The Experience of Perception

We may, however, get lost in theory, important though the theoretical questions are. Put otherwise, we need to bring our theories back to experience in order that they may be tested, and we must put questions to those experiences to see what they show us. What do we perceive? Think of something quite familiar to you: a house, an office, a person, a pet, a book. What informs your perception of it? How is it present to you? Have you ever been deceived about its reality through its appearance? Or about its appearance because of some belief you had?

As an example, allow me to quote from Douglas Adams’ comedic science fiction story, So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. One character, Fenchurch, is relating to another—Arthur—a memory of childhood.

“When I was a kid I had this picture hanging over the foot of my bed…. It was one of those pictures that children are supposed to like,” she said, “but don’t. Full of endearing little animals doing endearing things, you know?”

“I know. I was plagued with them too. Rabbits in waistcoats.”

“Exactly. These rabbits were in fact on a raft, as were assorted rats and owls. There may even have been a reindeer.”

“On the raft.”

“On the raft. And a boy was sitting on the raft.”

“Among the rabbits in waistcoats and the owls and the reindeer.”

“Precisely there. A boy of the cheery gypsy ragamuffin variety.”

“Ugh.”

“The picture worried me, I must say. There was an otter swimming in front of the raft, and I used to lie awake at night worrying about this otter having to pull the raft, with all these wretched animals on it who shouldn’t even be on a raft, and the otter had such a thin tail to pull it with I thought it must have hurt pulling it all the time. Worried me. Not badly, but just vaguely, all the time.

“Then one day—and remember I’d been looking at this picture every night for years—I suddenly noticed that the raft had a sail. Never seen it before. The otter was fine, he was just swimming along.”

How often do we worry about overworked otters? What precisely is happening when we look at such a picture? How does the (mis)interpretation happen? To help our reading and analysis of such questions, I recommend reading these few pages from Robert Sokolowski’s Introduction to Phenomenology.

What is the Reality of Perception?

Are the things we perceive real? What does that question mean? How are sense and perception related, how distinguished? What is the relationship between perception and understanding? These are all complex questions—and admit many challenges and difficulties.

Join our conversation this Wednesday (20 August 2025, from 5:45-7:15+ pm ET) and let us see what we can see—and what we do not see!

philosophical happy hour

« »

Come join us for drinks (adult or otherwise) and a meaningful conversation. Open to the public! Held every Wednesday from 5:45–7:15pm ET.

No responses yet