To appreciate how Dewey’s “progressive” educational model and Hutchins’ and Adler’s conservative or “classical” educational model were both inadequate responses to the technological environment of the 20th century – namely, the displacement of the print environment by the electric environment – it will be helpful to make a brief detour into the pioneering media analysis Marshall McLuhan began to develop in the 1950s.

For instance, after integrating his study of the liberal arts with a phenomenology (or “grammar”) of media forms, McLuhan would assert that the cultural supremacy of the printed book from the 15th-19th centuries fostered a mode of perception that was intensely dialectical, laying the ground for the decline of the grammatical basis of the classical trivium. As argued in McLuhan’s 1962 breakthrough book The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press circa 1440 amplified the social and psychological effects of phonetic alphabetic writing, the latter of which, as an analytical division of the units of speech in a neutral visual form, generated the perceptual conditions for the development of detached analytic reasoning in Ancient Greece from the 8th to 4th century BC.1 While, for centuries, such reasoning existed in harmonious tension with the imaginative, dynamic, and mystical modes of insight connected to the ancient oral tradition, the mechanical power of Gutenberg’s printing technology suppressed what was mysteriously alive but literally invisible in human experience by turning human discourse into infinitely repeatable commodities of linear and uniform visual text.

In contrast to the medieval manuscript, McLuhan recounts, the standardized production of such commodities – or ‘books’ – made reading so widely available and efficient that the collective experiences of ritual inherent to the oral tradition became displaced by the newly developing attraction of the intellect abstracted from reality, as found in the habitual practice of the isolated individual reading silently to oneself. As a result, the Ancient Greek and medieval sense of the individual rational soul actualized by grammatical and rhetorical customs of literary interpretation and civic virtue was overridden by the enshrinement of the single point of view (or “perspective”) of the isolated intellect. In the context of Enlightenment philosophies such as Immanuel Kant’s, it was precisely the atomized intellect, and its specialized command of dialectical method, that was imagined as reinforcing the efforts of other intellects in a continuous march toward a free, rationalized, and prosperous way of life – the Kantian “kingdom of ends.”2

Ironically, the ‘Gutenberg Galaxy’ would itself be put to an end by the technological progress ushering in electric communication media from the telegraph in the 19th century to radio and television in the 20th century. The transition from the print environment to the electric environment signaled, for McLuhan, a dramatic reversal (or ‘chiasmus’) in the very grammar – and thus sense of existence – of western culture. If print media engendered perceptions that were sequential, uniform, individualistic, specialized, and mechanical, electric media engendered perceptions that were simultaneous, non-uniform, group-oriented, holistic, and organic. Bearing greater similarity, therefore, to the oral culture of the ear than to the literate culture of the eye, communication driven by multidirectional electromagnetic fields, McLuhan writes, “accepts the simultaneous as a reconquest of auditory space. Since the ear picks up sound from all directions at once, thus creating a spherical field of experience, it is natural that electronically moved information should also assume this spherelike pattern. Since the telegraph, then, the forms of Western culture have been strongly shaped by the spherelike pattern that belongs to a field of awareness in which all the elements are practically simultaneous.”3

For McLuhan, this electromagnetic “reconquest” of “auditory” or pre-literate experience through the simultaneous interpenetration of multiple times and spaces meant that electric media retrieved not only the tribal or group-like dimension, but also the mythic dimension, of oral culture. Thus, just as, in electric communication, we are “[confronted by] multiple relationships at the same moment,” the structure of myth and mythic awareness, according to McLuhan, is to provide a “multilayered” pattern of intelligibility, in which “a complex historical affair…is recorded in a single inclusive image.”4 It is no wonder, therefore, that the mass media of the 20th century came to be dominated by advertising imagery, which, like the transformative group awareness of myth, “strive[s] to comprise in a single image the total social action or process that is imagined as desirable…[informing] us about, and [producing] in us by anticipation, all the stages of a metamorphosis, private and social.”5

In addition to this consumerist updating (or denigrating) of myth, however, the electric return to pre-literate awareness, according to McLuhan, promoted a generalized intellectual interest in the “collective postures of mind” produced by mythic activity, such that the pursuit of social progress in the human sciences drifted away from a model based on the self-moving intellect’s internal derivation of absolute reason – as in Kant – and toward one based on the evolving collective production of symbolic meaning. Thus, in contrast to the “unexampled access to aspects of private consciousness by means of the printed page,” McLuhan writes, “now anthropology and archaeology give us equal ease of access to group postures and patterns of many cultures, including our own.”6

Accordingly, following the ‘auditory’ character of electric media, whereby the mechanistic abstraction of print technology was replaced by the experience (even if mechanistically simulated) of organic and dynamic simultaneity, Dewey and his followers comprising the so-called “Chicago school of sociology” studied the human individual as a concrete and complex instantiation of biological and cultural evolution. Developing the 19th century social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer, Dewey incorporated the pragmatism of psychologist William James towards an experiential analysis of the symbolic interaction between self and environment that showed how, as Dewey’s follower Charles Cooley wrote, “society was an organism in a deeper sense than Spencer had perceived.”7 As Czitrom writes, “from James’s ‘objective psychology’ [Dewey] learned that mind is not an entity separate from its environment, but an objective process through which the organism interacts with the world around it. From Darwinian biology Dewey applied the notion of adaptive species to ideas; he ultimately defined a method of inquiry aimed primarily at adjusting the human species to its surroundings.”8

In light of McLuhan’s 1940s critique,9 therefore, it is clearly evident that, for Dewey, “the individual has no nature which is not conferred on him by the collectivity.” In light of McLuhan’s 1950’s investigation of media environments, however, it is not quite the case that Dewey’s educational program encouraged the specialization of disciplines that, as a product of the analytical stress of the print environment, came to undercut the unified learning of the classical trivium in the American university. In this sense, as Levine observes,10 Dewey echoed Hutchins’ Great Books program, which was based on the observation that the demise of classical education in the American university was due, not only to the isolation of academic disciplines on account of specialized scientific methods, but also to the excessive application of techniques of classifying and categorizing to classical texts themselves: “The [great] books had become the private domain of scholars… [P]rofessors were unlikely to be interested in ideas. They were interested in philological details. The liberal arts in their hands degenerated into meaningless drill.”11

Inheriting the electric media bias of dynamic simultaneity, Dewey similarly bemoaned the lack of communication between specialized academic departments, and observed that the different segments of 19th century school curriculum arose out of different historical circumstances and thus different and ultimately incompatible priorities. For Dewey, education needed to become an “organic whole”; he thus, as Levine notes, “sought to connect academic studies with everyday life, so what the student learns at school willy-nilly reflects the unity of lived experience.”12

Where Dewey’s critique of specialism departs from Hutchins’ is in the former’s reduction of truth to the organic and experiential, thereby arguing for a holism based, not on the classical literate exegesis of the Logos’ analogy of being, but rather on the electric media bias, whose oral simultaneity seemed to dissolve the ontological separation – or analogy – between the internal growth of mind and the external growth of matter or “earth.” Thus, as Dewey writes in his 1915 book School and Society, “all studies arise from aspects of the one earth and the one life lived upon it. We do not have a series of stratified earths, one of which is mathematical, another physical, another historical, and so on.”13

Dewey’s uncritical and unacknowledged adoption of the 19th century “reconquest” of pre-literate culture infuses his entire educational paradigm; the acquisition of truth, for students of Dewey’s program, is thus equated with the dynamic collaborative process of “evolutionary growth” achieved through the experiential problem-solving, whereby human life is rendered increasingly adaptive to – and sovereign over – physical, social, and technological environmental pressures. Far from being attained through the western literary tradition, therefore, knowledge is primarily gained through directly experiencing – and innovating upon – the manner in which one has inherited the impulses and interests, from archaic times to the present, that both reflect “man’s past most successful achievements in effecting adjustments and adaptations” and point toward a “form so best to help sustain and promote the future still greater control of the environment.”14

With this reduction of knowledge to evolutionary success (and power), truth collapses into myth. In other words, consonant with the electric media environment, existential reality loses its transcendental status as known by the human intellect and becomes identical to the socially-constructed narratives and symbolic codes, which, in the context of Dewey’s thought, manifest greater or lesser degrees of adaptability and control over the cultural environment. Through Dewey’s model, the seeds of postmodern cultural relativism become deeply embedded in the ideological makeup of American education.

What is particularly significant to the ‘technoclassical’ present, however, is how Dewey’s overall attempt to adapt humanity to the technological society of the early 20th century reveals a fundamental confusion of technologically generated attitudes. We have already seen how, qualifying McLuhan’s judgment, Dewey’s social scientific concoction of Jamesian pragmatism and Darwinian biology reveals a deep, though unacknowledged, commitment to the pre-literate ‘anti-rationalism’ retrieved by electric media. At the same time, however, McLuhan’s characterization of Dewey as a pre-eminent dialectician carrying forward the ‘Ancient Quarrel’ of the classical trivium is not exactly off the mark. For, while he embraces the organic, tribal, and experiential qualities of electric media, Dewey frames these within a rigorous devotion to the rational instrumentality and linear conception of human progress correlated to the print media environment. For instance, it is precisely in the student-led solution to social problems by way of an in-depth experience of specialized professions that society, through the enlightened dissemination of knowledge in modern media, might evolve into what Dewey termed an ‘organized intelligence,’ and, as with Kant’s ‘kingdom of ends,’ generate a democratic ‘Great Community.’15

Put in terms of media environments, the fundamental contradiction in Dewey’s program is that in following the electric environment’s reduction of existential truth and ultimate purpose to the dynamical experience of human groups, Dewey’s notion of social progress – itself derived from the rational essentialism of the print environment – prohibits any ultimate standard, or rationally apprehensible essence, by which such progress might be evaluated. Hutchins’ critique of Dewey’s educational aim is thus apt: “For Hutchins, Dewey’s notion of scientific inquiry is of the means/consequence variety: it does not posit absolute or final ends. There is no overarching teleology to which scientific inquiry aspires. It is purely instrumental, in Hutchins’s estimation. It cannot lead us beyond itself to an answer as to why we ought to choose one moral path over another.”16

Despite Hutchins’ incisive critique of Deweyan progressivism, however, it is evident that Hutchins and Adler’s ‘Great Books’ alternative suffers from the same contradiction – albeit reversed – inhabiting Dewey’s program. In other words, while the internal contradiction besetting Dewey’s program resulted from Dewey’s unacknowledged transplanting of the print environment onto the electric environment, we might say that the basic contradiction of the Great Books program results from an unacknowledged transplanting of the electric environment onto the print environment. Particularly, in fleeing the cultural relativism and ideological anarchy fostered by electric media, Hutchins and Alder end up reproducing the analytic abstraction fostered by print, while grounding this abstraction in the mythical aura generated by the culture of mass media.

Accordingly, in glaring contrast to his article “An Ancient Quarrel in Modern America,” McLuhan launched a fairly devastating critique of what he saw as the philosopher Mortimer Adler’s strong dialectical influence on the Great Books program. In opposition to the classical grammatical and rhetorical traditions, in which the encyclopedic knowledge of etymologies and figures of expression trained one’s sensibility to discern the living analogical order of the cosmic Logos, Adler, according to McLuhan, applied a strictly logical and analytical approach to the western literary tradition. In an unpublished article entitled “Failure at Chicago,” McLuhan thus criticizes the literary methods of Adler along with his Chicago colleagues Richard McKeon and Ronald Crane as neglecting the perceptual power of literature to provide living sustenance to the intellect: “there is no question in their minds of the curriculum as providing content or furniture for the human mind. For them a book is not nutriment. It is a bone to sharpen the teeth. A challenge to the dialectical method. A book is approached not as an experience but as a problem. It is not a world to be explored but a collection of arguments and strategies to be pinned to the mat.”17

McLuhan’s critique resonates both with Adler’s intellectual background, as well as reviews of Hutchins and Adler’s famous 54 volume Great Books of the Western World set published by the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1952. For instance, while completing a PhD in psychology from the University of Columbia, Adler developed a close friendship with fellow graduate student Arthur Rubin. Under the influence of Rubin, Tim Lacy writes, Adler began to regard philosophy as “a field where paradigms of the world were dialectically compared: no self-evident or undeniable truths were allowed. Everything was merely more or less possible, depending on the coherence of views being compared. Because Rubin shared this vision, coined by Adler the ‘philosophy of may-be,’ with Scott Buchanan, this view of philosophy ‘dominated’ Adler’s mind until the mid-1950s.”18

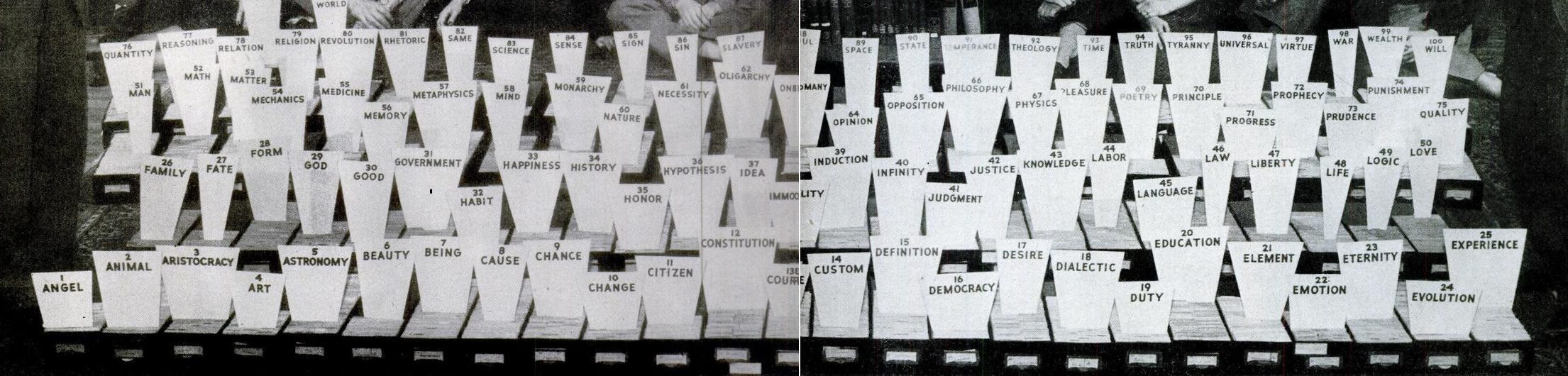

Adler’s reduction of literary tradition to the systematic comparison and categorization of ideas was perhaps most evident in his creation – through a funded staff of ‘indexers’ – of the monumental ‘syntopicon’ or ‘idea-index,’ in which 102 ‘Great Ideas’ were catalogued, introduced, and meticulously indexed in their appearances throughout the Britannica Great Books volumes. As aptly characterized in the New York Times Book Review in 1952, the syntopicon suggested “that great books are concerned only with ideas which can be logically analyzed – whereas many masterpieces of literature live in realms partially or wholly outside the realm of logic.”19 Likewise, as Lacy details, the historian Jacques Barzun commented that Britannica’s Great Books “betray a high-minded axe-grinding in the direction of intellectualism…[and] systems composed of analytic thoughts… This is important and indeed necessary to our lives as practical and reflective men. But a rational life based on no other kind of thought will almost certainly be – despite the editor’s assurance – a tyrannical order.”20

Paradoxically, such ‘tyrannical order’ driving Adler’s Great Books program derived not only from Adler’s rejection of the chaotic dynamism of the electric environment in favor of the fixed intellectual abstractions fostered by print media, but also from his propensity to render intellectual history susceptible to mythologization under the therapeutic framework of mass media consumerism. The conflation of dialectical method with the magical aura of advertising technique in the Great Books program is suggested in McLuhan’s parody of the syntopicon in his unpublished Typhon in America: “There is to be a big I.B.M index. Suppose you want the low-down on one of the hundred great ideas. Let’s say it’s ‘tragedy’. Turn up tragedy in the index and by gosh you’ll find listed every occurrence of it – at least in the great books selected by Professor Adler. In a jiffy you’ll have a cross-section of ‘tragedy’ through the ages.”21 Here, McLuhan reveals the fundamental irrationality buried within the logical mechanism of Adler’s ‘idea-index’ – namely, how an elaborate technology built for accessing ideas becomes its own source of spiritual fulfillment purely through the power of categorizing it bestows.

Such an interface between the print environment’s mechanistic rationalism and the electric environment’s irrational commodification of desire points to a significant phenomenon, whereby, as McLuhan notes, any medium pushed to its limit reverses into an opposite form. Applied to the print media environment (and its mechanical inauguration of assembly-line production), we might say that through the virtually endless generation of identical products to be consumed by the public, the nature of cultural production lost its rational utility and became grounded in the very act of consumption powered by a collective imagination tethered no longer to physical reality but rather to ‘the magic of advertising.’22

In this light, it is instructive that the Great Books program – and the ‘middlebrow’ democratization of culture it helped establish –23 derives from the Victorian era’s mixture of rational individualism with the swiftly increasing consumer remedies fantastically promoted in late 19th century print advertising. Analyzing the “therapeutic roots” of consumer culture, Lears explains how general “feelings of unreality stemm[ing] from urbanization and technological development” in the late 19th century helped develop a new secularized religion based on the promise of “harmony, vitality, and the hope of self-realization” through the marketing of such products as “patent medicines, toothpastes, and automobiles.”24 It is in this context that grew what Lacy describes as the Victorian “mania” of drafting lists of the best books so as to make the “genteel” character of high culture accessible to the masses. As Lacy writes, “from a heterogeneous mass of Victorian notions of reading, self-improvement, and time efficiency, as well as a general search for order, the great books idea emerged close to the form it would maintain through the twentieth century.”25

Comprised of print advertisements paired with satirical prose, McLuhan’s 1951 book The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man confirms Adler’s inheritance of this Victorian mindset by characterizing him as “an educator whose system and technique in education is itself an unintentional reflection of the technological world in which he lives.”26 Reflecting on Life magazine’s iconic representation of the syntopicon indexers, in which Adler stands to the left of numerous filing cabinets containing different “Great Ideas,”27 McLuhan pithily affirms how, far from retrieving the classical liberal arts for contemporary life, the Great Books program merely dreams up a fossilized past. The great ideas indexed in the Life photograph thus represent “headstones…alphabetically displayed above the coffin-like filing boxes,” exposing the unfortunate irony that “the present Life feature (January 26, 1948) should have so mortician-like an air – as though Professor Adler and his associates had come to bury and not to praise Plato and other great men.”28

While significant and incisive in itself, the fierceness of McLuhan’s critique of Adler points to McLuhan’s quest in the 1940s to produce his own version of the Great Books program with the help, precisely, of the president of the University of Chicago Robert Hutchins. In the next post, we will explore McLuhan’s 1947 proposal to Hutchins, wherein McLuhan seeks to establish an interdisciplinary “editorial community,” which, informed by the encyclopedic sensibility of the classical tradition, might “recover as much of the past as can be made creatively relevant to the present.”29 In this way, McLuhan would attempt to correct the moralistic avoidance of contemporary life, which he attributed, in a 1951 essay, to the ‘genteel’ Victorian Matthew Arnold – one of the key progenitors of the “Great Books idea.”30 As McLuhan asserts, if Arnold had such “insights and tools of analysis” that McLuhan aimed to develop, “Arnold might not have fallen into the trap of moralizing about the plight of culture in terms of an antecedent situation. He might have substituted precise diagnosis for moral alarm and exhortation. He might even have seen that the arts, at first banished to an ivory tower by an industrial age, were goin[g], for good or ill, to transform the ivory tower into a control tower with the help of the very technology which had begun by being so unfriendly to them.”31

- For an in-depth treatment of the gradual transformation of the Ancient Greek mind due to the effects of alphabetic literacy, see Eric A. Havelock, Preface to Plato (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967). ↩︎

- See Mary A. McCloskey, Kant’s Kingdom of Ends, Philosophy 51 no. 198 (1976). ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, Myth and Mass Media, Daedalus, 88, No. 2 (1959), 341. ↩︎

- Ibid, 339. ↩︎

- Ibid, 340-341. ↩︎

- Ibid, 343. ↩︎

- Daniel J. Czitrom, Media and the American Mind: From Morse to McLuhan, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 95. ↩︎

- Ibid, 103-104. ↩︎

- As articulated in his article “An Ancient Quarrel in Modern America” discussed in the previous post. ↩︎

- Donald N. Levine, “Dewey and Hutchins at Chicago,” in Dialogical Social Theory, ed. Howard G. Schneiderman (New York: Routledge, 2018). ↩︎

- Robert M. Hutchins, The Great Books of the Western World, Vol 1, The Great Conversation: The Substance of a Liberal Education. (Chicago: Enyclopaedia Brittanica Inc, 1952), 27. ↩︎

- Levine, 129. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- John Dewey, as cited in Thomas Fallace, Repeating the Race Experience: John Dewey and the History Curriculum at the University of Chicago Laboratory School, Curriculum Inquiry, 39, no. 3 (2009), 392. ↩︎

- See Czitrom. ↩︎

- James Scott Johnston, The Dewey-Hutchins Debate: A Dispute Over Moral Teleology, Educational Theory, 61, no. 1 (2011), 13. ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, The New American Vortex (V 4). “The Failure at Chicago”, n.d., Vol. 63, File 40, Marshall McLuhan fonds, 1871-1987, National Archives of Canada. ↩︎

- Tim Lacy, Making a Democratic Culture: The Great Books Idea, Mortimer J. Adler, and Twentieth Century America, PhD Thesis, Loyola University Chicago, 2006. ProQuest, 108. ↩︎

- as cited in Lacy, 214. ↩︎

- as cited in Lacy, 215. ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, Typhon in America, Book I: Know-how or Daedalus, n.d. Marshall McLuhan fonds, 1871-1987, National Archives of Canada. ↩︎

- See Raymond Williams, “Advertising: The Magic System.” In Problems in Materialism and Culture. London: Verso, 1980. ↩︎

- See Joan Shelley Rubin, The Making of Middlebrow Culture (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992. ↩︎

- T.J. Jackson Lears, From Salvation to Self-Realization: Advertising and the Therapeutic Roots of the Consumer Culture, 1880-1930, Advertising & Society Review, 1, no. 1 (2000). https://muse.jhu.edu/article/2942 ↩︎

- Lacy, 83. ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (London: Duckworth Overlook, 2011), 43. ↩︎

- https://forum.zettelkasten.de/uploads/editor/bi/p6ekifpu6gx9.jpg ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, Proposal to Robert Hutchins, retrieved from https://mcluhansnewsciences.com/mcluhan/2017/06/proposal-to-robert-hutchins-1947/#fn-40322-4 ↩︎

- See Lacy, 27-48. ↩︎

- Marshall McLuhan, A Federal Offense! The Varsity, 71, no. 55 (1951), retrieved from https://archive.org/details/thevarsity71/page/n459/mode/2up ↩︎

No responses yet