Why we need digital monasteries for the layman, and what that means.

The Roman Empire was inarguably among the greatest imperial powers ever to have existed. It spanned the breadth of all Europe, crossed into Britain, swept south along the Mediterranean, and held much of the world in order for hundreds of years. But over its latter centuries, its martial rigor and social cohesion declined, leaving the Western half to fall under barbarian invasion. Some of the barbarians took to Christianity, some to heretical forms of it; many remained pagan, and for centuries most remained content to ignore or spite the learning which had been nourished in the Greek and Roman civilizations.

Today we face a similar situation—in more ways than one. Aside from noting their reality, I will say nothing of the political parallels and contrasts. But our learning is no less imperiled today than it was on the cusp of the sixth century. Only, it is not barbaric illiteracy which we must fear (a raw disdain for learning), under which the West became dark and near-silent, intellectually, for a few centuries; but rather a kind of hyper-literacy that does not foster thinking but drowns out meaning and understanding with ceaseless noise.

To whom should we listen, when every voice projects itself into the maelstrom of opinion?

Sophistry: Barbarians Inside the Gates

What is a sophist? There are two answers to this question. One, it may be used to identify a group of historical figures in Grecian antiquity, men who were truly learned but nevertheless nihilistic, for whom their knowledge was an instrument to gain wealth and power. Two, it may be used more broadly to identify anyone who, alike to these Greek figures in intent but not necessarily in being learned, uses language (or other means of persuasion) to convince others that he or she has the answers to life’s difficulties or problems despite either not knowing or not caring for what is true.

Though the sophists of antiquity—famously challenged and oft-defeated by Socrates, as recorded in Plato’s dialogues—are long gone, we seem yet to have no shortage of sophists in the broader sense. I am not referring only to podcasters or pundits, but indeed to many of the most highly-credentialed figures from the most well-respected universities. The causes of such sophistical invasion are complex, multifaceted, and defy reductive explanation. For one, we can point to the Enlightenment’s emphasis upon encyclopedic knowledge as the hallmark of wisdom, which leads to technocracy. For another, we can identify the modern philosophical movement’s rejection of tradition and subsequent cherry-picking of texts and ideas. For a third, we can note the explosion of college attendance in the mid-20th century (subsequent to the G.I. bill) and the ensuing rapid expansion of credentialism.

Regardless of the particular causes, however, there are many today claiming knowledge who have little, and what little they have is quite shallow. To anyone familiar with the traditions of education in the Western world, the presence of this sophistry in the university has been evident for quite some time. Many of the sophists are, themselves, in fact, unwitting participants in the deviation; they have been themselves trained by sophists, who in turn were likewise trained in sophistry by their own teachers. This sophistry therefore persists not as the vice of this or that individual, but rather as a social condition affecting intergenerational conformity to declining standards of truth and wisdom.

Furthermore, our digital environment’s present dominant use—social media essentially giving everyone in the world a basic equal opportunity at gaining an audience while simultaneously favoring content that is shallow, quickly accessible and intelligible, and therefore incapable of demonstrating the reasoning involved—amplifies many of the worst claims (the most immediate attention-getting and least-thought-provoking) while suffocating the best (those that require careful reflection and a slow digestion). We live online under a persistent deluge of noise, opinions and responses everywhere, but not a true thought to think.

Liberalism or Charlemagne?

How do we restore a sense of intellectual order? Many, insensate to the violence of the sophistical welter in which we caught, believe we need only right the ship and sail on—that the ideal of democratic liberalism and its late-modern “marketplace of ideas” will suffice to restore wind to our educational institutions. This opinion seems strongly held by many an academic of older generations, those who rose to prominence in the 1980s and 90s, perhaps even into the early 2000s, whose careers in the universities may have been fraught with contention but who nevertheless were able to endure and even find some success.

Younger generations, however, do not share this optimism. They see beneath the damaged hull of educational institutions a deep rot within the political keel. It does not seem possible to restore the institutions as they are or have been. Riding out the storm will only leave one stranded on a ship doomed to sink.

Thus, they look increasingly for a political strongman, capable of sweeping away by force the old and rotten so that something new can be built up in its place—a Charlemagne. But such a figure is not only truly rare (not the “would-bes” but the actually successful), he is also hard to gauge in the moment. We will know him only by his fruits, which may take long to flower.

Yet the Carolingian Renaissance did not spring up from nowhere nor merely by the will of a great man. It was made possible by centuries of silent and dedicated work. The learning that spread during the eighth and ninth centuries from Alcuin of York and Theodulf of Orleans, and many others, was possible only because each was himself the coalescent result of long and arduous, and unglamorous work performed by countless monks unknown and seldom named.

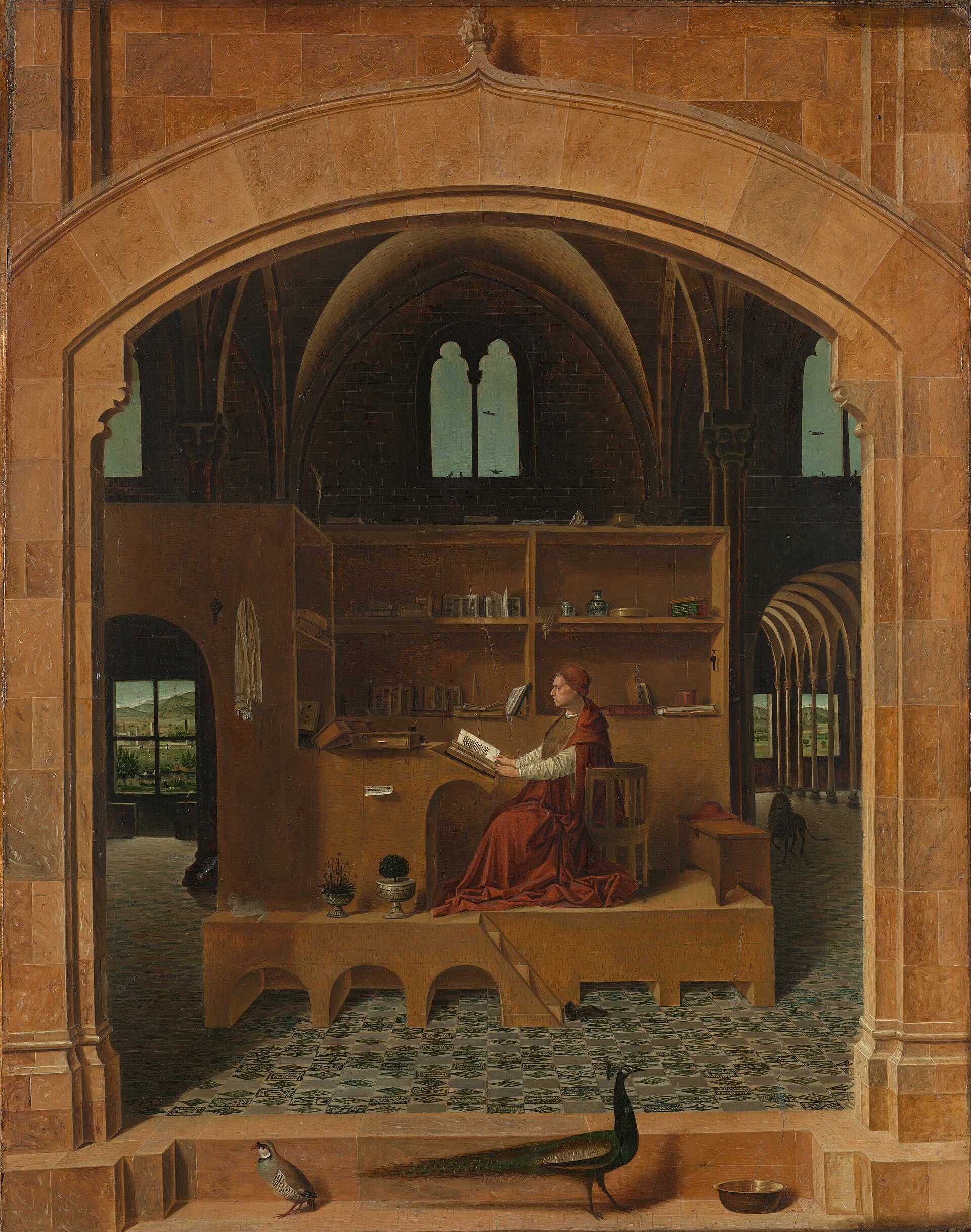

Silence of the Monastery

Between 500 and 800ad—and into the following centuries—the monasteries served as the principal bridge preserving the learning of civic schools in Roman and Greek antiquity and the later flourishing of Scholasticism. But their efforts, though often silent in the world of barbarian disorder, were not merely those of archival preservation and transmission. They cultivated an ordered life which saw learning and understanding as integral goods of not only the political but the spiritual life, as a fitting good for the human mind as created in the image and likeness of God.

Thus, in the sixth century, formal study became an expected and normal part of monastic life. The Rule of St. Benedict was not an academic program, but it did foster the habits of reading (lectio as a daily responsibility) and therefore demanded literacy of its adherents. Monastic reading was first aimed at Scripture and the Church Fathers, yet the practical requirements of reading well—grammar, rhetoric, and the basic tools of interpretation—naturally drew monasteries into the inheritance of late antique education. At roughly the same time, figures like Cassiodorus at Vivarium explicitly commended the copying and careful correction of manuscripts as part of one’s religious practice, treating the scriptorium as a kind of workshop of charity for future generations. This development is one of the period’s most important educational shifts: book culture ceased to depend on urban patronage and became, in many places, a monastic duty.

From this foundation grew the most visible and one of the most enduring accomplishments: the creation of durable scriptoria and libraries. Monks working in the scriptoria copied the Bible and patristic works with great frequency and diligence, but they also transmitted a significant portion of Latin classical literature—especially the authors most useful for teaching style and language (Cicero, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Lucan, Terence, and others, albeit unevenly and often in excerpts). Much ancient philosophy and science survived indirectly as well: not primarily through replication of complete Greek works, but through Latin mediations and compendia—Boethius for logic and parts of mathematics, Macrobius and Martianus Capella for encyclopedic learning, and later Isidore of Seville for a grand synthesis of “things and words” in his Etymologiae. The monastic habit of excerpting, glossing, and compiling—florilegia, commentaries, and handbooks—protected the content of fragile materials (by dispersing their words into many copies) and therefore allowed the spread of this learning from one center to another.

But the monasteries also developed the curriculum of the liberal arts—seeing their study as an instrument to deepened faith and understanding both. The studies of the trivium—grammar, logic (albeit lacking many of the most important texts of Aristotle until the twelfth century), and rhetoric—helped to shape habits of preaching and scriptural interpretation. Meanwhile, the quadrivium—arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy—served the computation of time (especially Easter) and therefore the liturgical calendar, the development of chant, the construction of ever-greater churches and cathedrals, and a disciplined contemplation of created cosmological order. These studies, developed throughout the centuries, nourished the life of the mind during the civic disorder following Rome’s collapse and allowed wisdom to spring up organically when political rule was re-established across the European continent.

Preservation and Order in the Digital World

The digital environment—still so new and yet already more pervasive than any technological framework in human history—has long been recognized as having a great archival capacity. The capacity to store ever-increasing quantities of data opens the door for preservation unlike ever before. But this door opens also to a kind of purposeless hoarding, as well. That is, a well-curated process of storage for reasoned transmission serves the purpose of preservation, of protecting and handing-down worthy knowledge. A chaotic process of storing everything, simply to store it, results in a cheapening, a flattening-out or leveling of all the things preserved. Abundance without order accelerates the decay of understanding, and access to everything all the time impedes one’s advance towards wisdom.

We can see this decay and impediment in the current dominant patterns of digital media use: eyes glued to screens looking for the latest details of a given situation, the constancy of interruption, the deluge of noise, the endless cascade of call-and-response mechanisms, the proliferation of easily-enjoyed but thoughtless content, the substitution of “infotainment” for genuine study, and so on. None of these patterns constitute a thoughtful preservation or a pursuit of genuine understanding and wisdom.

On the one hand, the indifference of the underlying digital technology disfavors perceptual discrimination and in particular the habit of “pattern recognition” which widely came to be considered the hallmark of intellectual acumen in the twentieth-century. (One sees an obsolescence of pattern-recognition as intelligence affected by the advent of “AI”—but that is another topic.) In short, no difference between the real and unreal in digital representation makes sense-perception in a digital medium highly suspect. On the other hand, this indifference demands sharper intellectual habits, so as to make the discriminations we need. Such discrimination has always been needed, in fact, but a willingness to trust in sensation obscured its necessity.

Thus, although the digital environment has heretofore been construed in a way contrary to the human good, it not only calls out for truly human habits of thinking, it also provides unique means to their accomplishment: we no longer need to congregate in protected, remote places in order to preserve wisdom, but can work through these technologies not only to safeguard vast troves of wisdom, but to build up again the ordered habits of mind by which they are truly understood—quiet minds, careful thinkers, honest inquirers working in bonded communities to read well, exchange ideas carefully, and to cultivate a respect for a living tradition of wisdom.

The Wisdom of Texts and of Tradition

It is tempting, in moments of cultural anxiety, to imagine that the mere recovery or circulation of texts, and even a broader exposure to them, will suffice to restore wisdom. And indeed, our shelves—so recently emptied—must be refilled (not only with digital simulacra, but the physical copies!), our syllabi re-drafted and revised, and—for the sake of continued renewal, yes, it is fruitful if the archives are digitized. Yet texts, and even courses of study in them, do not educate. They can instruct, provoke, unsettle—but they do not form the mind. Formation requires a manner of life within which texts are approached, received, and slowly assimilated. Without this, even the greatest works remain inert, or worse, become instruments of vanity and display.

The monasteries of late antiquity understood this expressly. Books were precious, but they were never isolated from the rule of life that governed their use. Reading was ordered, paced, and subordinated to a broader rhythm of prayer, labor, silence—and dialectical instruction. Texts were not encountered as consumable objects, nor as raw material for immediate opinion, but as authorities to be dwelt amongst. The wisdom that emerged was not located simply in the manuscripts themselves, but in the tradition of disciplined inquisitive attention that surrounded them.

This distinction matters because our present condition offers unprecedented access to texts while simultaneously dissolving the conditions under which they can be read well. The digital environment presents works of genuine depth alongside commentary, reaction, and polemic, all flattened into the same stream. The reader is encouraged to sample rather than submit, to skim rather than linger, to respond rather than reflect; to consume endlessly rather than to digest slowly. Under such conditions, even the greatest classics are absorbed into the noise they might otherwise have helped to quiet.

Tradition, properly understood, is not the passive inheritance of content but the active transmission of habits. It answers not only what is to be read, but how, when, and to what end. It establishes sequences—what must be learned first so that other, deeper, greater things can be understood later—and it imposes limitations, excluding much of lesser importance so that the things most important may be learned well. Tradition is thus not opposed to intellectual freedom, but rather a necessary condition of its righteous use.

The modern layman occupies a peculiar and historically novel position. He is neither enclosed by a rule of life nor guided by stable institutions of learning, yet he is constantly addressed as if he were already competent to judge all things: invited to participate in endless debates without having been formed in the arts of judgment, and drawn into one after another controversy without having acquired the habits of attention that make disagreement fruitful. The result is not independence of thought, but a subtle heteronomy: beliefs shaped by forces unseen and authorities unacknowledged.

To speak, then, of a “digital monastery” is not to propose a retreat from the world, nor to romanticize the past. It is to suggest that, under modern conditions, the preservation of wisdom may once again require spaces of deliberately-imposed order: places, whether literal or virtual, where thoughtful silence is encouraged, where reading is slow, where authority is earned by thinking rather than purchased through credentialing, and where the pressure to respond gives way to the discipline of understanding.

The monks of the early Middle Ages did not know the full extent of what they preserved. They labored faithfully within limits they accepted, and the fruits of that labor appeared centuries later. If our own age is to preserve anything worth handing on, it may depend less on what we say, or even what we store, than on whether we are willing to recover the forms of life in which wisdom can once again take root.

No responses yet