A Philosophical Happy Hour on why the study of signs constitutes the recovery of genuine philosophy and may result in the infusion of philosophical habits into culture.

Few words common in modern “intellectual” environments sound as sophisticated or are used as carelessly as “semiotics”. Given that it is often associated with French structuralism or deconstructionism, one might be forgiven for dismissing it out-of-hand. And yet, the true roots of semiotics are not found in the twentieth or even nineteenth centuries, but far earlier: no later than Joannes a Sancto Thoma (1589–1644—also known as John Poinsot) and in many ways as early as Augustine of Hippo (354–430). While it was not always an explicit concern of the Latin Age—nor made as central as perhaps it could have been—study of the sign nevertheless played an integral role in the philosophical development for those twelve centuries.

Where the weight of this proto-semiotic consideration fell most heavily was on the notion of the concept: that on the basis of which our minds attain unity with all the objects of knowledge. Thus, awareness of the sign influenced all the great debates between nominalism and realism in the Scholastic period. Recovering this awareness, then, will prove pivotal to the future of thinking.

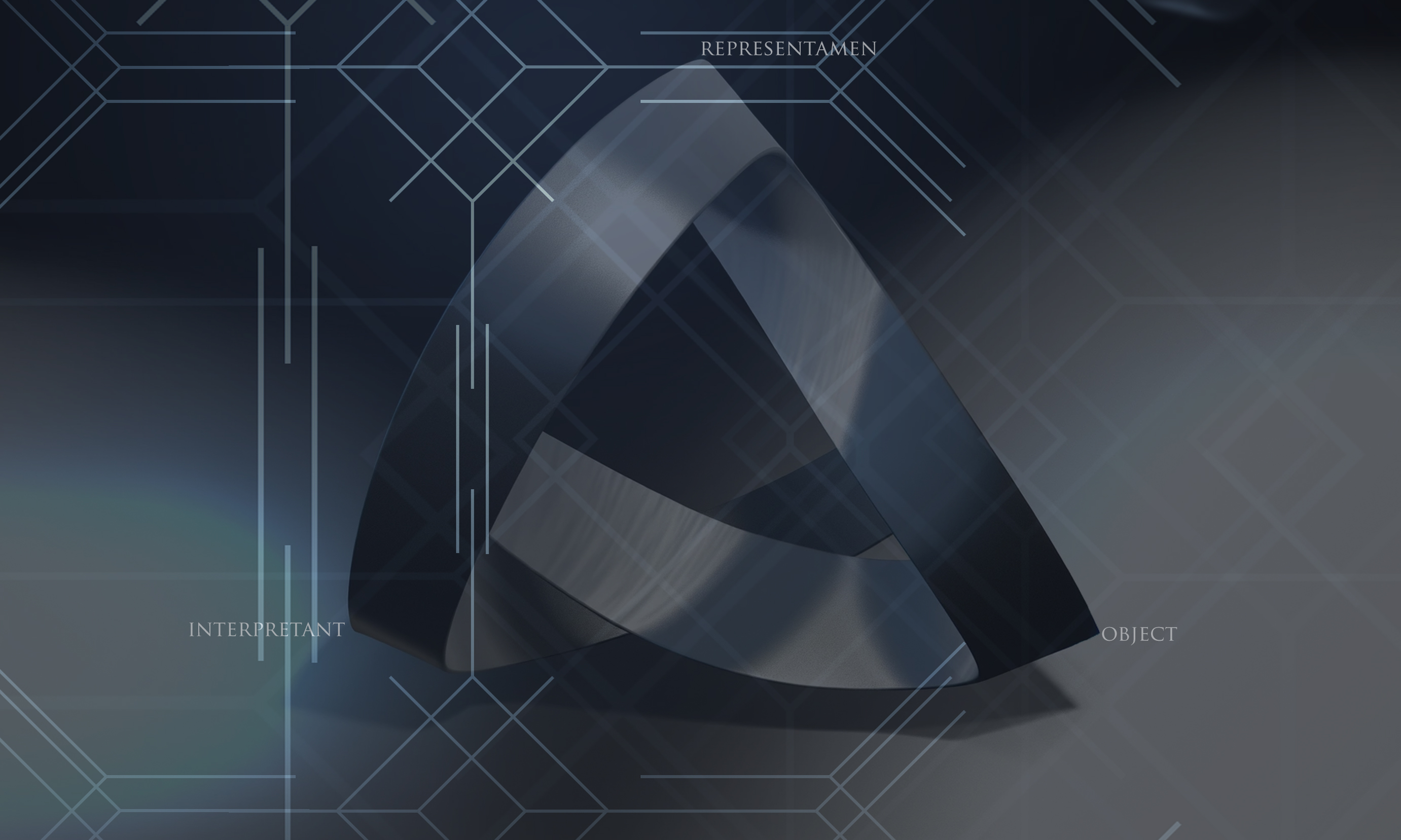

The Study of Signs

Although Latin Age semiotics reached a pinnacle in the mid-seventeenth century work of John Poinsot, modern philosophy (in the work of René Descartes) arrived on the intellectual scene at the same time—and went an entirely different direction. Some thinkers have justly characterized the modern period as not, indeed, philosophical, but rather an era of fictions, fantasy, and sophistry. It was not until the pioneering work of Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914), an ardent (if largely autodidactic) student of Scholasticism, that a study of signs would receive its due attention again; and Peirce was largely misunderstood and neglected in his own time, as well.

Yet, in recent decades, great attention has been paid to the Peircean doctrine of signs (thanks largely to Umberto Eco, Thomas Sebeok, and John Deely). Slowly, a revitalization of true philosophy—invigorated by this historical retrieval of not only Peirce but the Scholastic tradition—begins to dawn. The role of signs in this revitalization requires careful inquiry, for signs are easily misconceived and a failure to understand their nature and function properly could lead to countless and profound errors.

But… Why?

While this exhortation to the study of semiotics might seem important for the professional intellectual, why should the average person care? Does semiotics play a role in the life of the salesman, the doctor or nurse, the programmer, the accountant, the mother or father? Although a difficult subject to study, I would suggest that everyone can benefit from a better awareness of signs and how they function. First of all, it has practical applications across all disciplines, since all disciplines make use of signs in some way. Second, it elevates our understanding of relations of all kind, including between family members. And third, in many ways, it sharpens the intellect in much the same way as does studying logic—improving one’s capacity for reasoning.

I believe that this last is the principal good, however, that a study of semiotics accomplishes. Especially today, since we live in a world perfuse with cultural signs, do we need to be better reasoners. That is, the world of culture mixes truth and falsity, fact and fiction, narrative and fantasy. Signs create the world of culture, and one enters into the cultural world through the use of signs. But anything which we use that we do not understand has a way of being used against our own best interests.

Signs of Life

Please join us this Wednesday (29 January 2025) for our Philosophical Happy Hour (5:45–7:15pm ET; latecomers welcome!) as we strive to navigate the tricky world of semiotics! For anyone interested in a deeper dive, this 72-minute lecture does just that.

philosophical happy hour

« »

Come join us for drinks (adult or otherwise) and a meaningful conversation. Open to the public! Held every Wednesday from 5:45–7:15pm ET.

No responses yet